VAT Calculator

This value-added tax a.k.a. VAT calculator is a tool you can use to compute the amount of VAT you need to pay and the gross price of the product based on its net value. Besides, you may employ our calculator to add VAT or remove VAT to/from the net/gross amount. Before you use this online VAT calculator, you may want to take a moment to read more about the topic: what is VAT, what is its history, how to work out VAT manually, and what are its economic implications together with some interesting facts.

VAT definition

Value added tax (VAT), is a consumption tax; it is applied to goods and services, which is why it is known as goods and services tax (GST) in some countries such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Singapore. The name refers to the fact that it is a tax on the "added value", i.e. the sale price of a product after deducting the cost of materials and other taxable inputs (see below for an example). Another form of consumption tax is the sales tax.

What is the difference between VAT/GST and sales tax?

VAT/GST applies to every stage of production of goods and services (therefore called a multi-stage tax) and is calculated based on the "added value" only. It means that each participant in the production chain pays VAT only for the "added value" they create. This process goes on until the product reaches its final recipient — the customer. He/she does not produce any "added value", therefore it is he/she who is the ultimate bearer of the tax burden.

In contrast, the retail sales tax is a single-stage tax charged on the total value of sold goods or services when the sale takes place. Therefore it is paid only once in contrast to VAT, which is calculated multiple times.

Through a simple example, the below table illustrates the comparison between VAT and sales tax. Imagine a lumberjack cutting trees (without cost) who sells the wood (enough for one barrel) to a sawmill owner for $100. The sawmill owner cuts the wood into oak staves and sells it to the cooper for $150. The cooper then makes a barrel that he can sell for $300 to the retailer who eventually sells it to the customer for $350. The total VAT paid is $35 or 10% of the sum of values added at each stage. In the case of sales tax with the same 10% rate the paid tax is identical, however, it's assessed only at the point of sale to the customer.

Stage | Product | Price | Value added | 10% VAT | 10% retail sales tax |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | log | $100 | $100 | $10 | |

2 | stave | $150 | $50 | $5 | |

3 | barrel | $300 | $150 | $15 | |

4 | barrel | $350 | $50 | $5 | $35 |

Total tax | $35 | $35 | $35 |

The two crucial implications of the difference between VAT and sales tax is that VAT involves higher administrative cost as it is applied more broadly, but it is less visible to the ultimate consumer and thus might be more favorable from a political perspective (Wells and Slesher, 1999).

What is the difference between VAT and GST?

VAT and GST are often used interchangeably, though there are particular differences derived from their implementations. Both forms of taxes are present in multiple stages of transactions and based on the value added; however, VAT procedure is related to the production/distribution chain, in contrast to the GST which appears in the supply chain. In other words, VAT is linked to the moment of sales, GST is tied to the point of supply.

Furthermore, VAT is a tax on the final consumption of goods and services which is entirely borne by the consumer. In contrast, GST is a single tax on the supply of goods and services. Credits of input taxes paid at each stage are available in the subsequent stage of value addition, which makes GST essentially a tax only on value addition at each stage. The final consumer will thus bear only the GST charged by the last dealer in the supply chain, with set-off benefits at all the previous stages.

Besides, VAT is performed offline based on a summary regarding a specific period, whereas GST is performed purely online based on transactions. Moreover, in the VAT system, the seller is responsible for the collection of revenues, while in the GST scheme the purchaser is in charge of the records.

Another difference between the two systems is the matter of double taxation, that is present in the VAT regime, as the tax on the excisable goods might also be levied on the manufacturer. In contrast, excise tax within the GST is subsumed up; thus double taxation is not binding in such case.

Margin and VAT procedure

Some companies have the right to choose another form of VAT taxation called the VAT margin scheme. This VAT procedure allows companies to pay VAT on their profit margin on sold goods. In contrast to ordinary VAT, the seller cannot deduct VAT from purchased goods or services. If you need to know how to calculate your profit margin first you can use our gross margin calculator. If you want to use it in combination with VAT, try the margin and VAT calculator (it has nothing to do with the "VAT margin scheme", though).

How do I calculate VAT?

To calculate VAT, you need to:

- Determine the net price (VAT exclusive price). Let's make it

€50. - Find out the VAT rate. It will be

23%in our example. If expressed in percentages, divide it by100. So it's23 / 100 = 0.23. - To calculate the VAT amount: multiply the net amount by the VAT rate.

€50 × 0.23 = €11.50. - To determine the gross price: take the VAT amount from Step 3 and add it to the VAT-exclusive price. You get the VAT inclusive:

€50 + €11.50 = €61.50.

In essence, it's just a specific kind of net to gross calculation. If you want to do it quickly, simply use our online VAT calculator.

When can VAT be refunded?

There are circumstances when the paid VAT is refundable. Let's outline these situations associated with VAT paid in EU countries.

- Cross-border refunds to EU businesses: VAT paid during cross-border trades that are occasionally conducted between EU countries.

- VAT refunds for non-EU enterprises: companies not based in the EU can exclude VAT when they do business with EU countries.

- VAT refunds to foreign tourists: if you're about to visit the EU, it is worth knowing that you may be able to recover the VAT paid during your shopping.

You can find the VAT procedure and official guidelines on how to work out VAT refund on the following websites:

Value added tax in the United States

Despite the wide prevalence of VAT and GST over the world, the United States is the only individual member among the OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries without the establishment of a national-level valued added tax. Instead, sales taxes are levied and controlled at the state (sub-national) and local (sub-state) levels. At the moment, 5 of the 50 US states (Alaska, Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oregon) don't apply any sales-related tax.

The evolution of different tax systems depends on country-specific features and historical background, but also their economic systems. You can keep on reading, and in the following section, you will get some more insight on this subject.

Economic implications of the value-added tax

Benjamin Franklin in 1798 stated: "In this world nothing is certain but death and taxes." The eerie statement was declared not in vain: taxation is a prevalent feature of everyday life since its initial appearance — according to Burg (2004), it was Ancient Egypt around 2390 BC where the tax was first instituted and collected in the form of grains. With the advent of industrialization, the scope of tax policies gradually expanded and, by the 19th century, taxation was a part of nearly every type of human activity and consumption in more advanced countries. As government tax commonly accounts for a considerable part of government revenue, this change profoundly affected our financial affairs — VATs political and economic concerns became paramount.

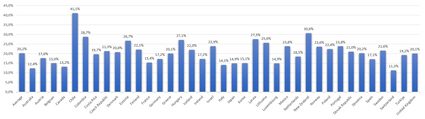

The following graph shows the share of VAT as a percentage of total taxation in 2020 through different countries.

The economic implications of taxation can change depending on the theoretical approach and the type of tax. Adaptation or modification of VAT structure — in scope or tax rate — can impact the economy as a whole through different channels:

- It may affect saving behavior

Economists, as common in a wide range of economic issues, often disagree on the implications of various tax burdens. The discussion on the choice between income tax and consumption tax constitutes one of these heated topics. A considerable part of the profession believes that income tax distorts savings behavior as it cuts earnings, thus reducing the disposable income (the part of income that is available after taxation) that people could devote to saving. On the other hand, a consumption tax emerges only when savings are spent; hence it doesn't alter saving decisions. Since higher savings contributes to higher investment, relying more on consumption tax may favor more for economic growth.

In the United States, government revenues depend more on personal income taxes compared to European countries, where consumption taxes make up the highest portion of government incomes. There were several attempts to move the US taxation system toward consumption-based taxation as advocates of such a shift argue that it would encourage individuals to save more. Higher savings then would foster economic growth in productivity and living standards.

In contrast, promoters of the present income tax believe that people wouldn't change much their saving habit in response to such a shift in the tax system. By addressing this concern, American policymakers adjusted the income tax law to compensate for such an adverse effect. Taxpayers can settle a limited amount on a special saving account (for example Individual Retirement Accounts and 401(k) plans) that is not subject to taxation until they withdraw their money during retirement. In such a case, people who save through these accounts eventually taxed based on their consumption rather than their income.

- It redistributes income in the economy

Firmly connected to the argument on the issue of saving behavior, tax laws which promote savings also impose more substantial weight on people with lower income. It is so because lower-income families usually can't afford savings and they tend to spend all their income on daily consumption; thus such a system reduces the tax burden on wealthier people and pushes the government to impose a higher tax on the poor. It follows that in countries where tax revenues heavily rely on consumption taxes, like a high VAT rate, it may widen the gap between rich and poor, thus increasing inequality in the society. The below figure shows the standard rate of VAT in OECD countries in 2022. The highest standard rate (27%) belongs to Hungary; however, it is compensated by reduced rates applied to foods and newly built homes to help the poor and support families.

- It can alter price levels

Implementation or adjustment of VAT rate may affect price level, though its magnitude and lasting effect depend on not only the design of the tax law but also the economic factors and reaction of economic actors to such a change. To see this, let's consider a rise in VAT rate in a country. The immediate effect of the change is certainly an increase in price levels of products that are subject of VAT; however, its inflationary effect may be mitigated if the seller doesn't transfer such a cost entirely to the final customer. Such a situation may happen in sectors where the competition is high among sellers or the consumer demand is more sensitive to price changes. In other words, the full price effect depends largely on the price elasticity of demand. Besides, the government may force sellers not to raise prices, thus implement a so-called price ceilings measure, that further dampen the price effect. However, even if a shift in VAT rate induces price change, the duration of the effect is rather short and hardly induce a sustained increase in the inflation rate.

- Automatic stabilizer

Since government taxes, in general, emerge from economic activities, their level depends largely on the realGross Domestic Product (GDP). The value-added tax particularly moves in tandem with economic production because of its consumption-based character. When income grows, people spend more on goods and services hence tax receipts automatically increase. In other words, a percentage of the total income produced in a country flows to the government depending on the economic activity: higher economic activity means higher tax receipts and lower GDP means lower tax revenue. However, as consumption forms a considerable part of GDP, most of this flows into the government, while a smaller proportion flows back into the economy (as a form of consumption) and contributes to economic growth. It follows that taxes can be considered as an automatic stabilizer since they protect the economy from overheating but also can support economic activity when the production is lower than expected. Besides, the government can boost consumption by reducing VAT rates; however, the effect of these policies are ambiguous and hardly long-lasting.

History of VAT

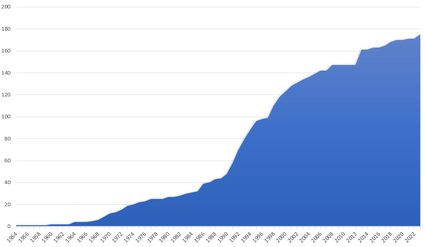

Compared to other forms of taxation, VAT, with only just over 60 years of operation, is relatively young. Nevertheless, it has become one of the most important sources of revenue for governments. The below figure show the number of countries having implemented a VAT.

There is no clear consensus on the exact time and place of the very first appearance of the VAT, however, most of the theoretical research and discussion begun in the 1920s in the U.S. and Germany. At this time economists proposed the VAT as a possible solution to gain substantial government revenue without distorting the resource allocation of the free market system (Lindholm, 1980).

A German businessman Carl von Siemens came up with the idea of the consumption type VAT in the 1920s, however, it was Maurice Lauré, the joint director of the French tax authorities, who turned Siemens's idea into a system and is considered to be 'the father' of VAT. Therefore, France was the first country to adopt the practice in 1954, although it was implemented in a slightly different way as it covered only the wholesale transactions. Shortly after, the VAT was also applied in former French colonies — Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal, and, in 1965, Brazil. Initially, the new tax did not gain much recognition. In the late 1960s, there were only 10 countries which implemented VAT into their tax systems. Its worldwide success was due to the expansion of the European Union, as adopting VAT was one of the prerequisites for membership. By 1989, VAT was present in 48 countries (primarily in Western Europe and Latin America), but with strong support from the IMF the number of countries implementing it grew to over 170. The present popularity of VAT stems from the fact that it is believed to be one of the most effective ways to increase government revenue. Another advantage of the VAT is that it is neutral toward international trade. Moreover, it is to some extent safe from domestic fraud.

What is the gross if net is $200 and VAT is 20%?

The gross price is $240. To arrive at this answer, we first calculate the amount of VAT as net price × VAT rate, so $200 × 20% = $40. Then we add this to the net price to get the gross price: gross = net + tax, so $200 + $40 = $240.

How do I calculate price before VAT?

To find the price excluding VAT:

- Determine the

VATrate. Write it down as a decimal number, e.g.,15% = 0.15. - Compute

1+ VAT. For instance,1 + 0.15 = 1.15. - Divide the

grossprice by the number from Step 2. - This is the net price, so the price before VAT was added. If you struggle with the computations, simply use Omni's VAT calculator.